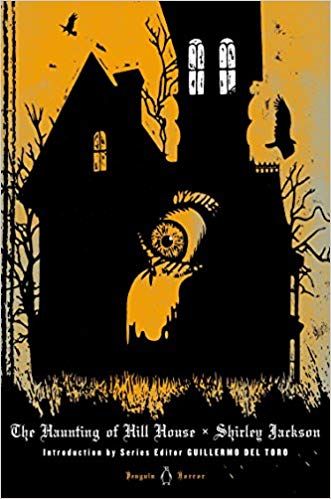

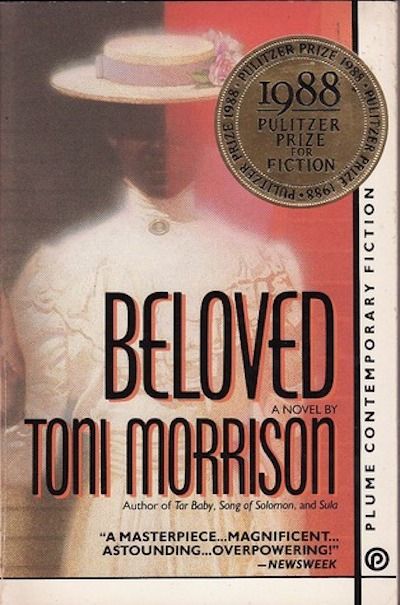

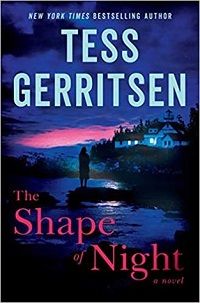

Let’s talk about haunted house boooooo-ks. If I had to pick one horror plot to read for the rest of my life, it would be the haunted house. No other plot offers such a wealth of storytelling options. It’s a recurring motif in horror literature, with some recognizable tropes and beats, but it’s also a plot made of Silly Putty. The more a writer pulls, the more it stretches, and they can stretch it in any direction they please. Why? Because a ghost is never just a ghost. Steven J. Mariconda described the haunted house story as “amazingly flexible” in its variety of themes, such as “good versus evil, science versus the supernatural, economic conflict, class, gender, and so on” (“The Haunted House,” Icons of Horror and the Supernatural, p. 269). In her critical study The Literary Haunted House, Rebecca Janicker adds to that list “capitalism, consumerism, domestic turmoil, and race” (11) and goes further to posit that the motif of the haunted house “affords a distinctive type of literary encounter with ideological forces, one tied to specific socio-historical contexts through the physical spaces in which hauntings occur” (11). Put simply: A ghost is never just a ghost, because it always represents something more than itself. Something that you try not to think about. Something unpleasant you try to ignore or repress until you can’t any more and it rises up to — quite literally — haunt you. Perhaps one of the best examples of this phenomenon is Toni Morrison’s harrowing novel Beloved. Like all the best ghost stories, it’s ambiguous in its approach. You are constantly left wondering if the ghosts in question are real, or projections of the trauma of Sethe’s past. And is a ghost any less real if it is in fact a memory? Or are all ghosts memories? Grady Hendrix wrote a wonderful piece about Beloved’s place in horror history for Tor.com’s blog a few years ago, and in it he describes ghost stories as being “about one thing: the past. Even the language we use to talk about the past is the language of horror: memories haunt us, we conjure up the past, we exorcise our demons.” Sethe’s guilt, the brutal violence she encountered in her life as a slave, and a history of racism that continues to haunt this country even today; all these things are the ghosts of Beloved. In The Haunting of Hill House, another classic haunting novel, Eleanor’s anxieties and the emotional trauma of her shuttered life lived at the beck and call of her overbearing mother are either the source of or a source of energy for the forces that roam Hill House (depending on your reading). In Tess Gerritsen’s The Shape of Night, the ghost that haunts the main character punishes her for the guilt she feels for fatal mistakes in her past. In Helen Oyeyemi’s oft recommended White is for Witching, family history, family secrets, and race all serve as an impetus for the haunting of the Silver family home. Hauntings come from us. From, as Hendrix pointed out, our past, and our fears, our sufferings, our longings, and our rage. We make ghosts of things that leave scars. Whether they be on us, on the physical locations where they took place, or on the world. And just like scars, ghosts linger long after the initial pain has passed. They poke their fingers into our weak spots and the places where we still hurt. Maybe that’s why I can’t get enough of ghosts. These days the past is a contentious issue. If you try to right — or even just acknowledge — the wrongs that left nothing but suffering and hatred in their wake, you’re “destroying the past.” But to ignore the dark, ugly corners of history entirely is to permit them to happen again and again, and never learn from our mistakes. And I guess for some people, that’s rather the point. The past is a lot prettier when you’re wearing the rose colored classes of “the way things used to be.” I think that’s why, like Hendrix said, we “conjure up the past” with ghosts: so that we never forget. If the past is full of violence, pain, and injustice, then like hell should it rest in peace. Maybe we deserve to be haunted.