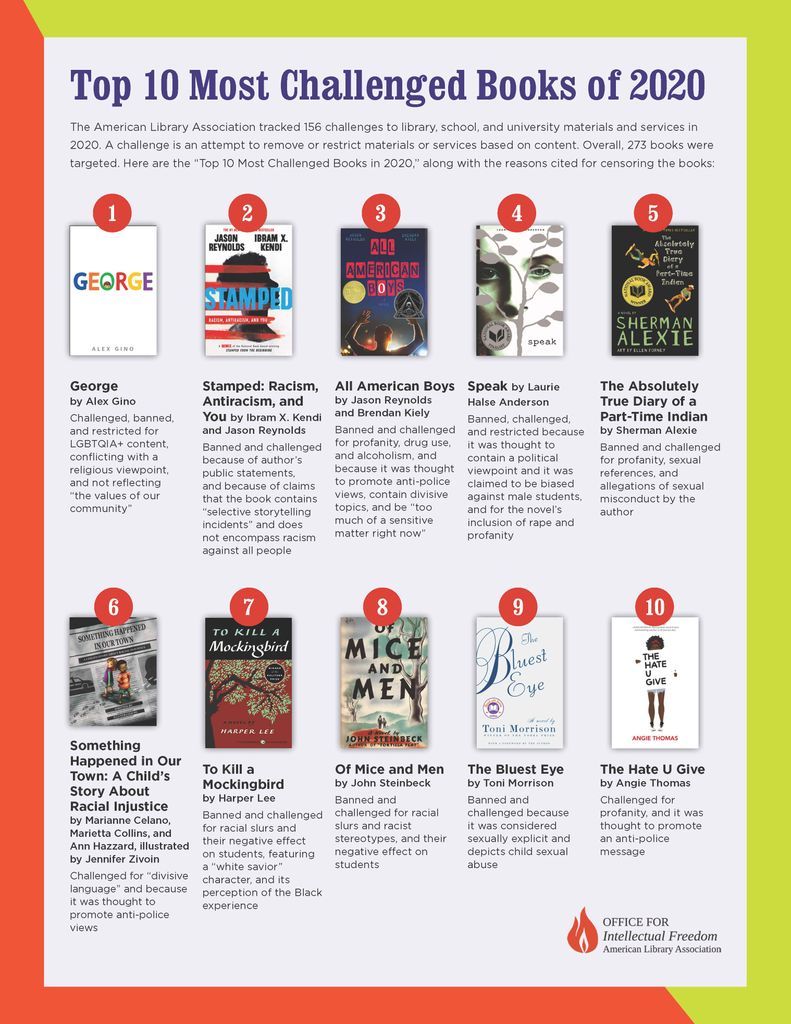

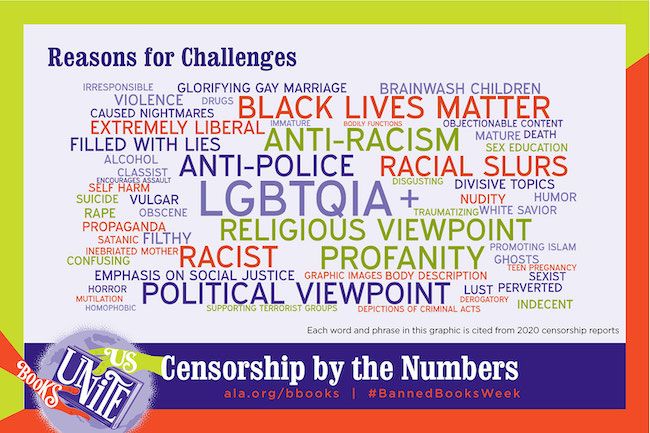

If you want to see the most diverse widely circuited book list online, it’s reliably the ALA Most Challenged Books list. This list is always filled with LGBTQ books and books by and about people of color, particularly Black people. This is 2020, though, so things look a little bit different from previous years. For one thing, 273 books were targeted in 156 challenges, while last year it was 566 in 377 challenges. These challenges happen mostly in schools and libraries, and since they were closed for much of the year, it makes sense that the number would decrease overall. There’s also a distinct change between the kinds of books targeted in 2020 challenges versus 2019. You can read the reasons for each challenge at the ALA website, but here are those 2020 titles again: For comparison, here is the top 10 from 2019: While 2019’s list was dominated by LGBTQ books, especially trans books (eight out of ten have prominent LGBTQ content, including four trans books), 2020’s list mostly deals with race and racism or “anti-police” content. In a backward way, this is encouraging. The fact that these books are being challenged enough to make it onto this list means they’re likely being brought into more libraries and classrooms. With George Floyd’s murder and the ensuing protests, many educators promised to make antiracism a bigger part of their curriculum. This list suggests that may have been true, even if it did result in backlash. Not all the books challenged for reasons of race on this list have the same reasoning, though. Alongside books like The Hate U Give being challenged for an “anti-police message,” books like To Kill a Mockingbird are being challenged for “racial slurs and their negative effect on students, featuring a ‘white savior’ character, and its perception of the Black experience.” This list shows two sides to an ongoing conversation about race in the U.S. and how Black people are being represented. Does this mean that LGBTQ books are being challenged less than last year, though? Not exactly. As the word cloud above shows, LGBTQIA+ is still the most commonly-cited reason for challenging a book. So why are those books no longer on the list? I would expect that it’s because the same antiracism books are being used across the country, while there might have been more variety in the LGBTQIA+ books being used and challenged. While books dealing with race are being challenged more in 2019 than they were in 2020, that hasn’t mean there was a decline in challenges for LGBTQIA content. After all, George has continued to be the most challenged book overall for three years running. At least, these are the patterns that I see. If you look at how this list is reported on in different outlets, you’ll see very different frameworks for it. I align with The Guardian‘s headline: “Sharp rise in parents seeking to ban anti-racist books in US schools.” The School Library Journal notes the top entries: “‘George’ Tops Most Challenged List for Third Year in a Row: ‘Stamped’ Takes No. 2 Spot.” The Chicago Sun-Times, though, takes a different approach: Most criticized books of 2020 include works by John Steinbeck, Harper Lee, and Sherman Alexie.” That might be literally true — they do make the list — but they are low on the list, and none of those are the Black authors who have seen the biggest increase in challenges. “Most criticized” is also inaccurate: a book challenge is an “attempt to remove or restrict materials or services based on content.” Criticizing a book is not the same as restricting it. Other lists mention the books most “objected to,” which is another euphemism. I object to many books, but I don’t try to have them restricted. I am always interested in the ALA most challenged list, because it reveals what conversations are happening across the country — not only in which books get listed and why, but also in how the list gets talked about. While many right wing outlets derided the “cancellation” of Dr Seuss, there doesn’t seem to be any reporting there about these antiracist books and their “cancellation” attempts. This list shows that both sides of this argument are trying to have books taken off shelves or curricula, each with their own reasoning. Of course, this isn’t the full picture. The Office of Intellectual Freedom compiles this list using media stories and voluntary reports that are sent to them, but they estimate about 82–97% of documented book challenges go unreported and are therefore not tallied in the results. That’s not counting all of the undocumented, unofficial ways that these books leave the shelves (or never make it these in the first place), whether from teachers and librarians who are too afraid of backlash to stock them, administrators quietly making the call not to teach them, or many similar occurrences. We need to be vigilant not only in calling out obvious censorship, but also in challenging our internal prejudices and fears that might have the same end result. If you want to help the Office of Intellectual Freedom, you can donate so that they can continue this work. Want to learn more about book banning and censorship? Read these:

QUIZ: Is it Censorship? The Statistics of Censorship Why and How Censorship Thrives in American Prisons The Banned Books archives