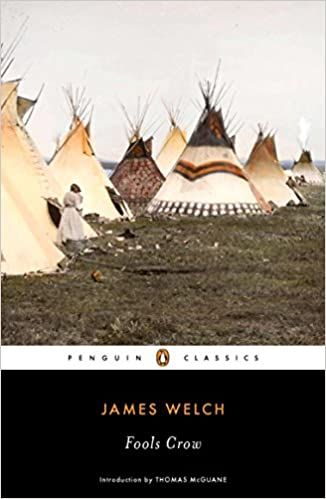

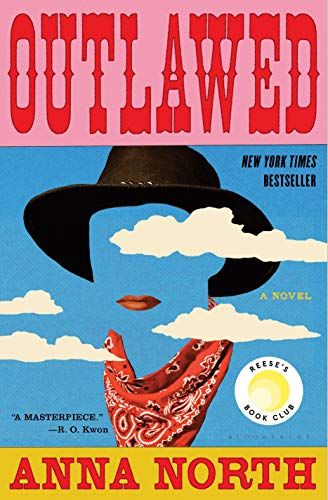

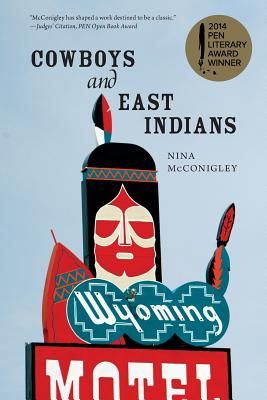

Like many popular genres, westerns first took off in the mid-1800s during the era of penny dreadfuls, which serialized a book over monthly publications. For readers fascinated with the expanding American west, the novels provided tales of adventure in a new setting, as well as a way to conceptualize a rapidly expanding nation. Many scholars of the genre consider The Virginian by Owen Wister to be the first “official” western novel. Published in 1902, it tells the story of an unnamed narrator who arrives in Wyoming from “back east” and takes a job as a ranch hand. Over time, he becomes a foreman on the ranch, falls in love with the local schoolteacher, and wrestles with the temptation to best his nemesis. These situations and characters, notably the remote Wyoming setting, sparked the imaginations of readers living in the “back east” that Wister described. While Wister’s novel was far from the first take on the frontier adventure story to appear in print, it’s become a classic for its themes of ranch life and the image of a determined yet controlled hero who is ultimately concerned with fairness and behaving like a gentleman. The Virginian put in place what came to define westerns: a lone wolf type hero on the frontier, who must maintain his honor, pursue justice, and ultimately ride off into the sunset. From the early novels of the 19th century, the genre continued to gain popularity, mainly as frontier mythology gained more and more ground in the American imagination. With the westward expansion of the U.S. government, it naturally followed that there would spring up a new form of writing devoted to the stories surrounding this expansion. The west itself plays a crucial role in most westerns, with sweeping vistas and dusty towns that often lead to long spells of loneliness for our hero. The western genre also provided a means of grappling with what westward expansion meant for relationships between settlers and those who already lived in their overtook territories. One common trope of the western novel is a Native American character, who is either portrayed as the wise sage side player to the principal white character or as a nameless savage who symbolizes the wildness of the frontier, in contrast to the civilization that the main character supposedly represents. Similar treatment is given to characters broadly portrayed as Mexican, who are often cast in bandit roles or in some other way that implies they contribute to the lawlessness and violence of the frontier. After the early years of westward expansion narratives, the western picked up steam with the gangster and train robbery novels of the 1920s. It maintained its popularity throughout most of the 20th century, peaking in the 1960s during the golden age of western books and movies, television shows, and comic books. With the Cold War simmering in the background, Americans were hungry for heroes, whether cowboys or Superman, who exemplified a set of values seen as trumpeting the American cause. Over the next few decades, movies like High Noon, series like The Lone Ranger, and books like True Grit gradually gave way to the new westerns of the 1980s and ’90s. Writers like Louis L’Amour and Corman McCarthy gained traction with books that exemplified the genre and went beyond its traditional confines. For example, McCarthy’s 1992 novel Blood Meridian is known for being one of the first westerns to portray the violence and depravity of western towns through the eyes of a teenage boy living on the U.S.-Mexico border. The subversion of the American mythology in these novels marked a sea change for both western writers and their audiences, who were increasingly moving beyond the lone wolf hero stories to ones with more morally complex characters. Also driving the changes in the genre was the drop-off in reader interest. After a glut of western media in the 1960s, new genres, such as science fiction, began to take center stage. The popularity of westerns faded continuously through the 1990s and up to the present. Also marking a significant change in the genre was the introduction of “adult westerns,” AKA cowboys (and cowgirls) having sex. While some looked down on this deviation from the traditional form of the novel, the adult market for westerns was one of the few consistently strong areas of growth for the genre in the 21st century. It would be easy to dismiss westerns as stereotypical stories of westward expansion: classic hero narratives remixed for American audiences curious about adventures on the frontier. But like all genres, there’s a variety of authors and plots under the western umbrella, with writers like Anna North and James Welch redefining what it means to be the main character in a western and the bounds of the genre. Additionally, new splinter genres, like western fantasy and sci-fi western, have arisen, giving readers more options than ever, and events like the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering showcase emerging authors in the field. If you’re ready to take a deep dive into the genre, you can check out Book Riot’s westerns archive or start with the five books rounded up below for an overview of both classics in the genre and new releases that shake things up. Ultimately, I believe we read both for entertainment and to answer questions about what it means to be human and what connects us. Just as science fiction books might help us figure out our relationship to technology, or horror might help us navigate fear, westerns appeal to readers because they explore key questions about justice, American mythologies, and our relationship to the history of the American west.