My mom, not having any of that, ordered every S.E. Hinton book she could find. In my house, I read anything I wanted to. Anything. It’s safe to say I’ve been a bookworm all my life. What’s more bookwormish than breaking the library rules? Than having a book confiscated after getting caught reading in the middle of math class? Than that sweet delight of reading under your covers by flashlight after your parents have declared it’s bedtime? I can think of only one thing greater. Maurice Sendak told the story of a little boy who once sent him a letter. In response, Sendak drew an original Wild Things illustration and sent it back. Sometime later, he received a response from the little boy’s mother. She wrote, “Jim loved your card so much he ate it.” Sendak said this was the highest compliment he’d ever received. May we all aspire to be as bookwormish as little Jimmy, consuming the words we hold so dearly. Devouring them. It can be said, for many of us I think, books are our life’s blood, the things that keep us afloat from the rest of the heaviness of our lives. Every reader I meet has a book that changed their lives and a story that goes along with it. Bookworms are a dedicated brood. And it isn’t just in English that you’d wear a label if you, like Jimmy, consume words the way you drink water: as if it is necessary for survival. No, in Danish, they’d call you a reading horse. In French, the decadent ink drinker. In German, you’d be a read-rat, a Romanian library mouse, an Indonesian book flea. Across the world, if you are a devourer of books, there exists a term for you that says: you are an animal who needs to eat, your food is words and you are insatiable. But where does our namesake come from? And when? My favorites are “reading horse” and “chapter maggot” pic.twitter.com/hgjIrRMakv — Nick Kapur (@nick_kapur) June 27, 2020

The First “Bookworm”

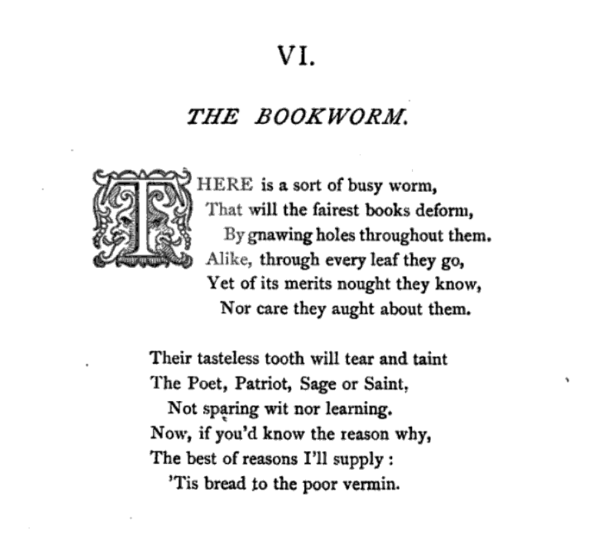

The earliest documented appearance of the word bookworm, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is in 1580. It appears in Three Proper and Witty Familiar Letters, a series of correspondences between scholar Gabriel Harvey and poet Edmund Spenser. One of the men writes of someone reading too much, “A morning bookeworm, an afternoone maltworm.” In Ben Jonson’s Cynthia’s Revels; Or, The Fountain of Self-Love, published in 1600, the word appears again with, “heart, was there ever so prosperous an invention thus unluckily perverted and spoiled, by a whoreson book-worm, a candle-waster?” While today’s use of the word doesn’t necessarily have an entirely negative connotation, it did then. Those who were bookworms were “candle-wasters” and “maltworms,” a reference to being an alcoholic. The 1988 Study on Integrated Pest Management for Libraries and Archives, says, “Phillippus of Thessalonica early in the first century A.D. compared satirically the grammarians of that day to bookworms, thus first voicing a comparison now used so often that instinctively one thinks of a very studious person as a ‘bookworm.’” Is this then, the birth of the term’s meaning?

“Bookworm” the…Worm?

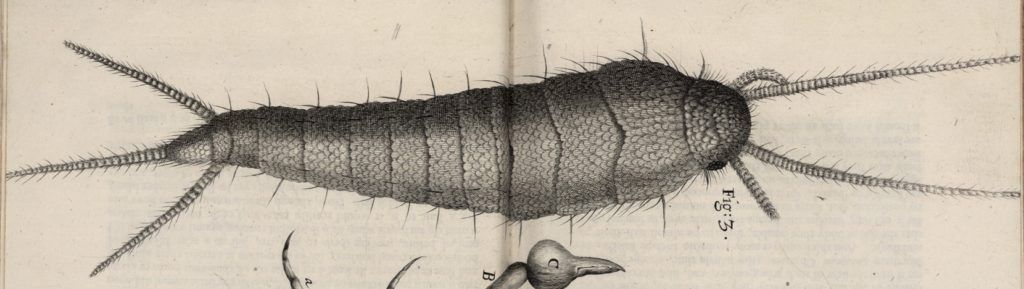

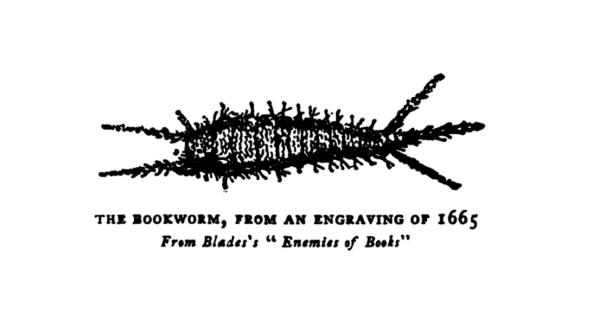

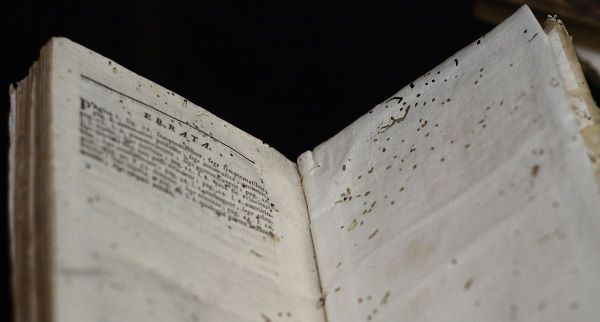

In 1654 the definition changes. In Richard Whitlock’s Ζωοτομία, or Observations on the Present Manners of the English, he writes, “Book-worme is of all Creatures the longest lived, the last in every Age living all the former, to whose Age Methuselahs was but Nonage.” Not in reference to a reader of books, but a creature in and of itself. So, what came first, the worm or the wise man? It’s difficult to say. While this is the first instance the term “book-worme” was used to describe the insects that eat their way through our beloved books, references to the hungry creatures appear centuries before. Aristotle’s History of Animals, dating back to the 4th century, described “the smallest creature of all” in “books”, like the “scorpion without its tail, exceedingly small.” Poet Evenus of Paros, around in the 5th century, wrote an epigram against the creatures: According to Cat Lambert in The Ancient and Entomological Bookworm, a papyrus from Roman Egypt described a dispute about damage done to an archive that was “σητοβρότα” (worm-eaten) Fruits of the Muses to taint, labor of learning to spoil; Wherefore, O black-fleshed worm! wert thou born for the evil thou workest? Wherefore thine own foul form shap’st thou with envious toil? Lambert goes on to explain the way Ovid in his Epistulae ex Ponto alters “ore populi,” the mouth of the people, to “ore tineae,” meaning the mouth of the bookworm, as he discusses fears of his work’s longevity. As quoted in 1924 by William Reinicke’s The Insidious Bookworm, Cynewylf, a poet in the 9th century, writes in his Riddles of a moth found eating books, “‘Tis a marvelous wyrd,’ he thinks, that a worm should devour the speech of men, and that this thief in the dark, this robber-guest, should be no wit the wiser for his eating.” Exeter Book‘s Riddle 47, dated back to the first half of the 8th century, has the solution book-moth or bookworm. Robert Hooke’s Microphagia of 1665 describes these insects saying, “It is a small white Silver-shining Worm or Moth, which I found much conversant among Books and Papers, and thus suppos’d to be that which corrodes and eats holes through the leaves and covers.” — Eleanor Parker (@ClerkofOxford) October 29, 2016 He calls this insect “one of the teeth of time.” While the word bookworm appeared first in reference to bibliophiles, its insect counterpart has existed just as long as books have.

Bookworms: The Insects

Despite the name, it turns out bookworms are not one singular insect. The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 20, published in 1898, points out “the expression ‘the bookworm’ is often used; but it is inaccurate, for some seven or eight species, perhaps more, actually do commit depredations in books.” Sir William Osler identified “67 species” that he called bookworms according to W.L. Holman in 1939. And, it’s not just worms. Or, worms as we think of them today, I suppose. Worm, according to The Pharmaceutical Era, can mean any creature “of a smallish kind that scuttles, wriggles, or crawls; and with this notion is blended an idea of voracity and omnivorousness.” Under this bookworm umbrella fall the larvae of many kinds of beetles, booklice, moths, cockroaches, and silverfish, as described by Hooke. Attracted to the damp, coolness of libraries much as we human bookworms are, these insects often gravitate to book bindings, glue, or molds that may grow on the pages we love so much. Sometimes, too, these insects, mostly termites and ants, begin by eating through bookshelves before doing any damage to the pages themselves. Beetles — such as woodboring beetles, augur beetles, bark beetles, and more — often do their damage while they’re in their larvae stage, burrowing into the books after they are laid on a novel’s edge or spine. Skin beetles munch on leather-bound books, preferring their taste. As if counting down the demise of your precious pages, the book louse, much like the death watch beetle, produces an “ominous ticking.” How, the author of The Pharmaceutical Era wonders, can “so small and tender an insect can create so loud a sound.” Termites are the most dangerous for our bookish obsessions, having a voracious appetite for every part of a book and the shelves they live upon, too. They’ve taken collections down in their wake, according to rumor. Under this definition of the creature, Emma Solberg in Human and Insect Bookworms: Post-Medieval writes, “If a cockroach nibbles on the corner of a book, then it becomes a bookworm.” — Dr Lizzy Lowe ❤️🕷️ (@LizyLowe) July 4, 2017 Little Jimmy, by this definition, is a bookworm too. Though I suppose we already knew that.

Co-Habitation?

Librarians and bibliophiles of the pre-modern era were resigned to sharing their libraries. Solberg writes, “Lucian called libraries ‘lodgings for worms’…Isidore of Pelusium agreed: ‘Books furnish a home and nourishment to the worms, and are vanquished.’” It’s during this period of co-ownership that “human bookworms began to identify with their insect counterparts.” See, some book lovers “liked to disparage other, rival species of bibliophiles by identifying them as bookworms.” It seems readers have always butted heads over the right way to read, like those today who argue against dog-earring pages. An epigram by Antiphanes, alive in 388 B.C., “compares grammarians…to ‘σῆτες’ [‘bookworms’], ‘the bane of poets’” The same way Cynewulf writes of his discovered moth no wiser for his eating, Symphosius and Exeter condemn readers who live in books but never improve, who take in the words, but never learn. Bookworm wasn’t quite the lighthearted teasing it is today. But, it’s very clear this association between the insect consumers and the human ink drinkers existed long before the word bookworm ever appeared to describe them.

The Enemy of Books

In 1744, The Royal Society of Science in Gottingen posed a challenge with a prize for the answer to the questions: “How many insects are inimical to libraries and archives? What kind of material do these insects like best? What are the best means of defence against them?” Then, 98 years later, The Society of Bibliophiles of Mons posed just the same. These little creatures, it seems, kept returning for more. Despite the fact the war already waged against them, in 1880 William Blades, bibliophile and collector of books, declared bookworms an official “enemy of books.” The title stuck. In 1911, The Museum News’s October issue for the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences announced a new exhibit: Enemies of Books. In the same vein, and the same year, The University of Pennsylvania held an exhibition of books “injured” by insects. “By all rights,” Solberg writes, “books belong to them more than they do to us.” Perhaps we are the enemy to bookworms, if that’s the case, ever obstructing them from their rightful homes. After all, “bookworms live in the archive; we just visit.”

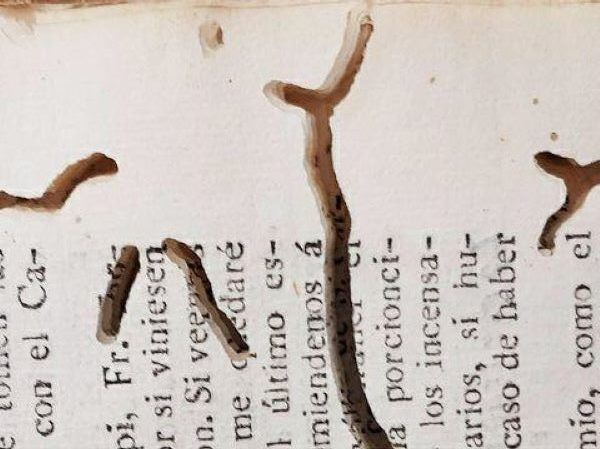

The Damage of Bookworms

The damage these insects leave behind varies. They can burrow through a book in one long line, eat across individual pages, or up the spine, leaving the pages weakened in its wake. Blades, declarer of bookworm’s enemy status, told the story of a series of “twenty seven volumes…pierced in a straight line.” According to Solberg, the entomologist William Reinicke describes books “‘so bored through with holes that the page looks like a sieve’; leaves that ‘when held up to the light, resemble pieces of rare lace’; a codex that, ‘as you grasp it, you are covered with a miniature snow storm of paper flakes’.” The damage would have been beautiful, if it hadn’t been wrecked on our precious books. A study by Stephen Hedges in 2013 revealed “two kinds of wormholes,” the lines caused by larvae and “round exit holes” made when the beetles emerge as adults. In fact, the damage of bookworms was once thought to make a manuscript authentic. So much so, dealers were suspected of faking wormholes in the 19th and 20th century with “white-hot awls and auger drills.” “In one case, magnifying lenses discovered fractures in the paint around the apparent wormholes of a Madonna and Child attributed to Botticelli, proof of a forger’s drill rather than an insect’s mouth.” These enemies of books, it goes, were kept as pets by some to do exactly what horrifies us so: to eat.

Eradication and Prevention: Back Then

No longer resigned to coexisting, methods emerged to eradicate these pests. Vitruvius’s De architectura advised libraries should face east as “facing south and west, books are damaged by bookworm and the damp.” “The meticulous librarian of Hereford Cathedral, believed that insects would not infest books that were kept in use, and so made a point of picking up, dusting, and vigorously shaking the codices under his care once each day,” writes Solberg. In the same vein, The Pharmaceutical Era’s author declares the “best cure would be to put the books themselves to their legitimate uses.” Books, after all, spend a majority of their long lives not being read. Years ago, some experts recommended, to great shame, burning the infected books. “Poison paste,” camphor, and other chemicals were tried, too, though covers are still found with holes bore through them. They tried seasonal methods, “Rub the books in March, July, and September” with pepper and alum and cloth. — Horniman Museum and Gardens (@HornimanMuseum) May 27, 2014 But, “unsurprisingly, it turns out that the poisons that hurt bookworms hurt books and librarians too.” Solberg’s “Human and Insect Bookworms“

Eradication and Prevention: Now

Despite Blade’s attestation that novels residing in the United States were left untouched, the “American writers” who “say so” lied. The assurances that a bookworm wouldn’t “deign to feed on a popular novel” were, too, proved wrong. Rumors, according to Solberg, that declared only neglectful bibliophiles the target of these teeth of time as “a just punishment for collectors more interested in display than study and a natural death for outdated volumes” were also false. Bookworms can, have, and do go after any page in their path much like their human counterparts. Now, libraries have developed their own methods of bug eradication that’s safe for their human counterparts. Some use heat, but exposure to higher temperatures can speed up the aging process in books. Instead, in 2012, The University of Washington noticed bed bugs on some of their returned books. In response, they developed a protocol to freeze the books for seven days. They emerged undamaged and bug-free. Should you open your favorite book and find, inside, one of these enemies of books, don’t turn to the flame. “Despite all the tall tales told about bookworms (volume-sets turned to tatters, entire shelves pulverized to dust), wormholes, as a rule, do not render texts illegible…Bookworms’ little negative doodles and tiny punctuation marks rarely obscure meaning.” Now, when you’re called a bookworm for reading during a Christmas party or for having a book in your bag no matter where you go, you’ll know exactly where your namesake comes from. As Solberg writes, “It is as if human and insect bookworms were meant to read together.”