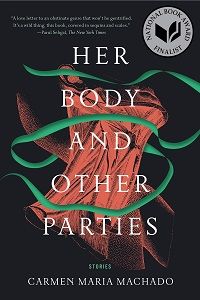

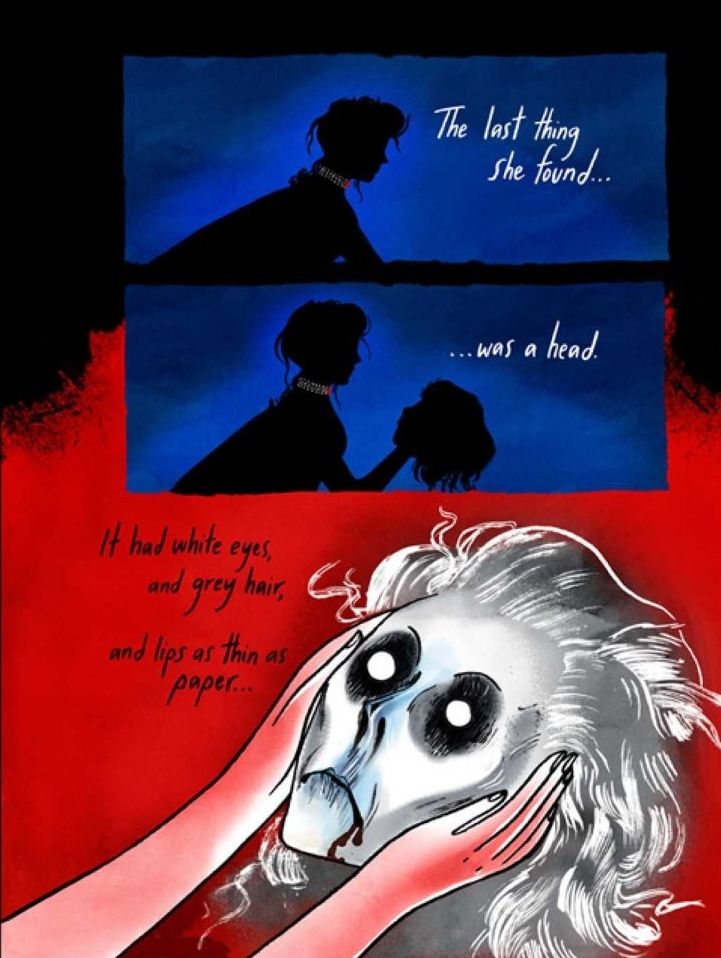

Bestselling authors Natalie D. Richards and Darcy Coates bring us stories that chill us to the bone and keep us up all night reading—haunting reads perfect for Halloween! A hitched ride home in a snowstorm turns sinister when one of the passengers is plotting for the ride to end in disaster in New York Times bestseller Five Total Strangers. From USA Today bestselling gothic horror author Darcy Coates comes The Haunting of Leigh Harker, a chilling story of a quiet house on a forgotten suburban lane that hides a deadly secret… “The Girl with the Green Ribbon” is a title many cite as a story which has never, ever left them. In it, we get a love story between Jenny and Alfred. Jenny always wears a green ribbon around her neck, and every time Alfred inquires about it, she tells him that she will let him know when the day is right. The couple eventually marries and Alfred never once sees Jenny without the ribbon around her neck. When she’s finally on her deathbed, Jenny reveals the secret of the green ribbon. She invites Alfred to untie the ribbon and immediately, her head falls off her neck and rolls to the ground. Schwartz was influenced by classic horror stories, as well as urban legends, so it’s not a surprise that “The Girl with the Green Ribbon” has a long history. Some origins date it back to the French Revolution, though there’s no question the story has been around in oral tradition since at least the 1800s. Alexander Dumas told a version of the story with “The Woman With the Velvet Necklace,” and years later, Washington Irving told it as “The Adventure of a German Student.” Scholars note that many readers might be familiar with Dumas’s title attached to Irving’s version of the story, as it was anthologized with both over time. Children’s author Ann McGovern told the story in a 1970 ghost story collection, Ghostly Fun, titling it “The Velvet Ribbon.” In 1977, Judith Bauer Stamper included a take on the tale, also called “The Velvet Ribbon,” in her children’s collection Tales for the Midnight Hour. “The Green Ribbon” is the kind of story which becomes an archetype in our collective imagination. It’s likely that many of us who heard the story and were frightened by it early on held onto those very memories of fear. For some, it was a turnoff to horror and for others, the very thing that made horror so appealing. The repulsion, the disgust, and the sheer terror of the idea that someone’s head is being held on by but a ribbon scratched a particular itch for the unimaginable. There’s research behind why horror stories are appealing, and when it comes to ways in which “The Green Ribbon” has clawed its way into our collective memories might have to do with what it says about our culture. We don’t like when people do certain things that are not “normal” or perceived as outside common behavior, and in the case of Jenny and her previous iterations, that fear is founded because it’s clear she’s not human in ways that we expect. Her head doesn’t stay attached except for the ribbon she can’t remove. “The Girl With the Green Ribbon” crosses backgrounds, though certainly, it’s landed more in white, Euro-centric storyteller hands. But Dumas brought his spin to the story, as have more modern and contemporary storytellers. The story in recent years been brought to fresh context, imbued with current sensibilities, and explored with a feminist lens. Carmen Maria Machado takes a spin on the tale in the first story of her debut collection, Her Body and Other Parties. “The Husband Stitch” plays with the story in an unbearably clever and equally devastating manner. A “husband stitch” is a procedure after a person gives birth where, in the process of repairing tears and lacerations to the vagina, an extra stitch is added to create “tightness” for the birther’s partner. Machado explores the notion that a woman’s body isn’t for herself and that even in one of the most intimate human experiences, her body belongs not to her, but to her partner, as his desire outweighs her own biology. Of course, the woman in the story dons the green ribbon and discovers that she has no agency in her life and that her body becomes a tool for patriarchal ownership. As her neck falls, she feels the weight of loneliness and the entire weight of what it means to give yourself over to the whims and desires of a man. Resolve runs out of me. I touch the ribbon. I look at the face of my husband, the beginning and end of his desires all etched there. He is not a bad man, and that, I realize suddenly, is the root of my hurt. He is not a bad man at all. And yet – – Do you want to untie the ribbon? I ask him. After these many years, is that what you want of me? His face flashes gaily, and then greedily, and he runs his hand up my bare breast and to my bow. – Yes, he says. Yes. – Then, I say, do what you want. One of the reasons the Schwartz story sticks is its effective use of illustrations. We see the woman, the green ribbon, and the resulting release of the girl’s head from her neck. It is eerie and simultaneously delightful in its creepiness. It’s not surprising that the effect of the story is powerful when rendered entirely as a comic. Emily Carroll does this in “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold,” one of the horror stories in her comic collection Through the Woods. A nameless girl is told by her father she is to marry a man she didn’t know. Without the ability to say otherwise, she is dashed off to the castle where the man lives and quickly made to fit the royal role into which she’s stepping. The maids wrap a ribbon around her neck as part of her ensemble, and the first night after dinner, she begins to hear a voice. The story unravels as the husband puts a fancy necklace around the woman’s neck and she, unable to stop hearing the voice, begins to look for the source, only to discover the decapitated body of another woman. The red ribbon connects the two as the new wife builds the body of the dead woman back together with it — only to be warned to get out because her life is in danger, too. Carroll’s art is dark and shadow-filled, with the song sung by the dead woman sprawled across the page spreads, much like her body and blood. Like Machado’s take on the tale, Carroll offers a warning to women in love (or forced into it): it may not be all that it seems. And indeed, we know from the start that the narrator’s body doesn’t belong to her, but it is instead a prop shared among men — first her father, then her husband. It’s fascinating to see the story of the ribbon play out across generations, with today’s readers most familiar with Schwartz’s take (and thus, the comments across fanart sites, reddit, and other forums noting memory of the ribbon being green and being scared to death by the story). But more, this is the kind of story with tremendous width and power. Machado and Carroll illustrate this well, developing entirely fresh and haunting stories that harken back to a long-told classic. They are not, of course, the only ones to do so, and indeed, especially as the writers most influenced by Schwartz’s story continue to create, we’ll experience more iterations of this story through even more diverse lenses: what does the story say about race, perhaps, and where are there cross-cultural tales that weave together similar elements? What does the story hold in regards to sex and relationships? Further, “The Green Ribbon” is a classic example of a story traversing generations. What began as an oral tradition morphed into works by classic, canonical western writers — all male — until the story got the children’s book treatment by two female authors. But it wasn’t until it was revived again for children that it took up real estate in our minds and psyches. And since Schwartz’s publication, we’ve seen only deeper dives into the possibilities, into the meaning, and into the future for what it is we ourselves may be holding onto by a ribbon of fabric, be it red, black velvet, or green.