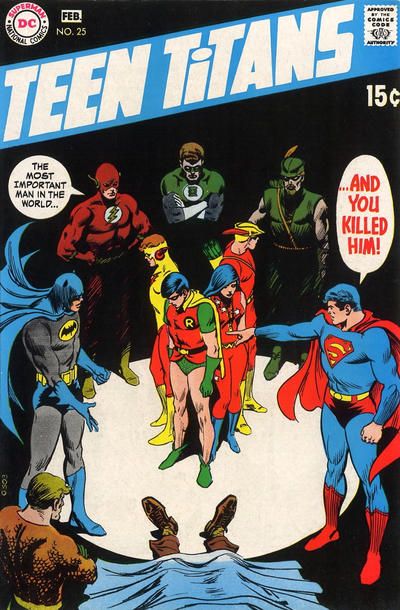

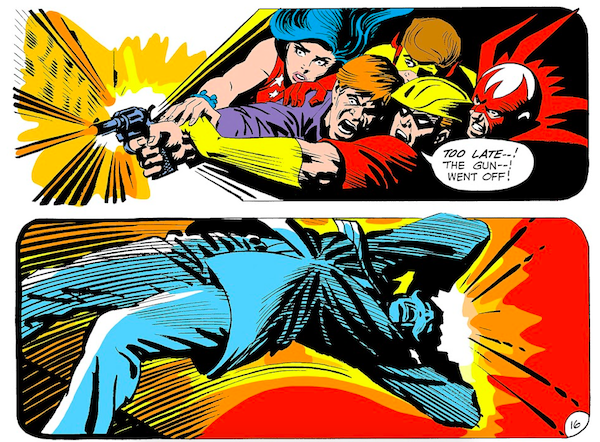

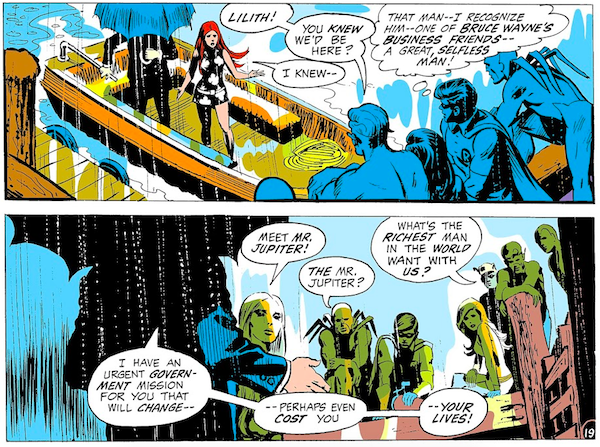

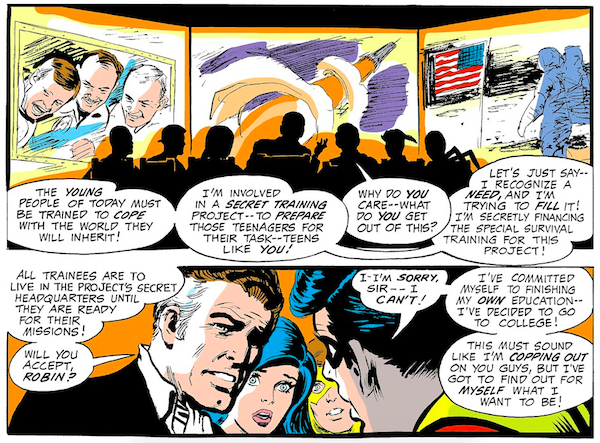

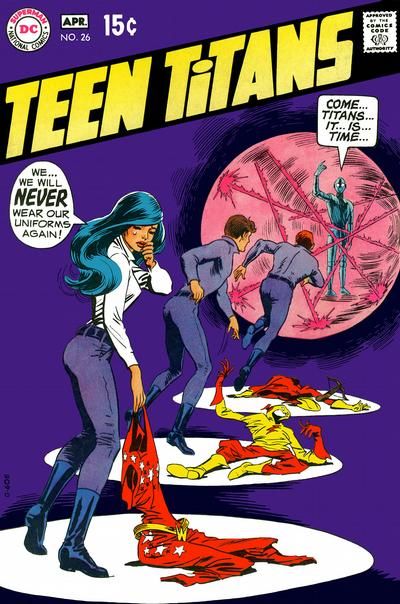

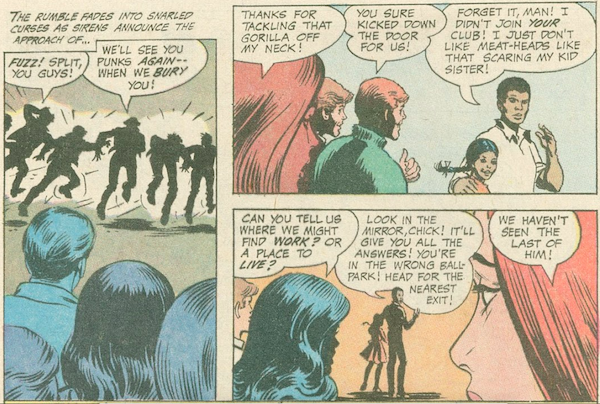

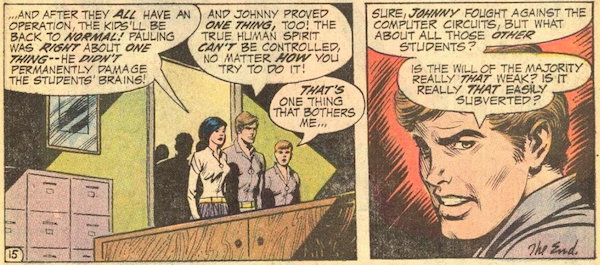

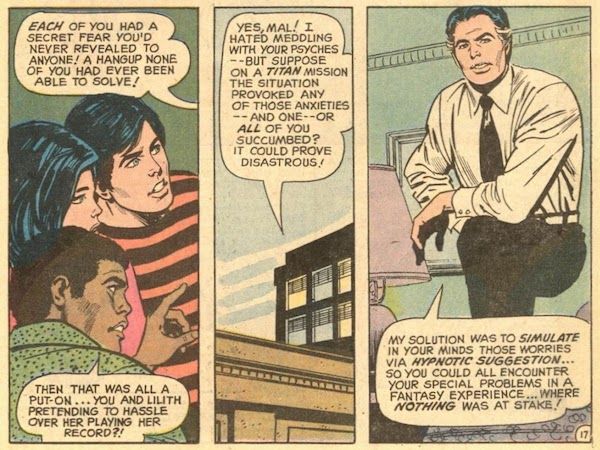

By the end of the decade, however, awareness had crept in at DC that young people were thinking about more serious topics than the Twist and which Beatle was cutest. And so the Titans very abruptly got Relevant. And it was real weird. The big change comes in Teen Titans #25 (February 1970), with a ludicrously dramatic cover and the equally dramatic title “The Titans Kill a Saint?” (Answer: only for the loosest possible definition of “kill.”) Events begin with the Titans (Robin, Wonder Girl, Kid Flash, and Speedy; original member Aqualad is MIA) in a nightclub with the implausible name of the Canary Cottage. There they meet Lilith, at which point the boys are all appallingly sexist and bafflingly racist. I truly cannot tell if Lilith, “the Enigma of the East,” was meant to be Asian in this comic — the dialogue seems to imply it, but she will be very clearly white in literally every other appearance from here on out, so who knows? Lilith, who has vaguely defined psychic powers, identifies the group as the Teen Titans and demands to join the team. They angrily deny it and refuse, even when she warns them that they are about to “open the door for death,” and storm out of the club. Outside, they run into a massive protest outside of a peace rally, at which the main speaker is Dr. Arthur Swenson, beloved Nobel Peace Prize winner. When the protest turns violent, Robin, I guess, forgets he’s a superhero and runs off to get the cops, while the rest of the Titans attempt to intervene, along with Hawk and Dove, superhero brothers who coincidentally happen to be on the scene as well. One of the pro-war protesters pulls a gun. The Titans and Hawk grab him, trying to disarm him — and the gun goes off, fatally wounding Dr. Swenson. Everyone promptly blames the Titans, which is extremely contrived. Swenson histrionically calls them “living atom bombs” before he dies, and the Justice League shows up to yell at them for “reckless use of [their] powers” even though Speedy’s only “powers” are “shoots arrows” and Robin’s are “not actually being present at the time.” Guilty and miserable, the kids head down to the docks for some reason, where a motorboat conveniently approaches carrying the mysterious Lilith (serving an absolute Look), and “Mr. Jupiter,” “the richest man in the world,” who knows everything that’s just gone down and cryptically invites them to come with him. The Titans agree, which: DON’T DO THIS. OH MY GOD. Jupiter tells them that he’s involved in a secret project training young people to cope with the world they will inherit, which absolutely sounds like paranoid prepper rhetoric that the Titans should run away from as fast as possible. Robin’s like “Um…I have class in the morning, but thanks” and immediately bails. I guess his power really is getting the fudge out of dicey situations, which…good for him, I guess, but maybe he should tell his pals about stranger danger? The rest of the Titans cheerfully hand over their costumes to a robot named Angel and put on matching lavender jumpsuits before riding a moving sidewalk through a portal marked “Survival Course — DANGER” that of course leads directly to a death trap. None of these kids has the self-preservation instincts God gave a gnat, I swear. Jupiter rewards them for surviving the death trap by sending them to “Hell’s Corner, the toughest neighborhood in the city” — an obvious reference to New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen — to find jobs and lodging and also accomplish another secret goal which he won’t tell them. But he does provide them with a single penny each to help them, with the warning that if they can’t use these pennies to succeed, he’ll be severely disappointed. Cryptic missions coupled with ominous threats of disappointment? This is masterful manipulation straight out of the cult leader playbook, and that’s before you take into account the raging daddy issues every superhero sidekick comes pre-equipped with. In Hell’s Corner, the kids immediately run afoul of a white gang called the Hawks (not to be confused with actual Teen Titan Hawk, I guess). They’re rescued by the intervention of local teen Mal Duncan — DC’s first Black superhero — who kicks the Hawks’ asses before telling the Titans to get out of Hell’s Corner. However, after the Titans later rescue him from the Hawks, he begrudgingly agrees to hang out with them, and the Titans realize that this was the secret second part of their assignment all along: making a Black friend, regardless of whether or not the Black person in question actually wants to be befriended. It’s all very uncomfortable, and only made more so when Mal agrees to join the Titans/cult on the condition that he doesn’t get a matching jumpsuit or a codename because he doesn’t feel worthy of them. Mal, you are ten times better than any of these dingdongs, I promise. Although I guess the less deeply you’re sucked into Jupiter’s horror show, the better. The weirdness of all of this is finally called out in issue #28, when founding member Aqualad returns to ask the Titans for help on a case involving Wonder Girl’s former roommate Sharon, who’s being menaced by hitmen (from outer space, naturally). They explain that they can’t do superhero stuff anymore because one time some guy died while they were also there; Aqualad is unimpressed. He’s also not too thrilled with Robin, who has been off at college and ignoring all this nonsense, and whose reaction to the whole thing seems to be “not my circus (where my parents died tragically), not my monkeys.” (Though he will eventually rejoin the team, while Hawk and Dove will just sort of…go away.) Eventually the Titans do agree to help and poor Sharon is saved, after which the Titans sort of forget about the jumpsuits, but they continue living with Mr. Jupiter, because he’s going to help them Change the World. …Except, well, he doesn’t. Once the Sharon plot is resolved, the remaining 14 issues of the series are overwhelmingly regular superhero stuff: The Titans go to the moon and meet aliens! Lilith discovers that she’s the reincarnation of Shakespeare’s Juliet, who she does not seem to realize is a fictional character! Kid Flash and Mal go back in time and accidentally kill a caveman, changing the timeline and turning everyone in the present day into a wizard (obviously) (also they rescue the caveman and name him Gnarrk and he joins the team)! There’s a heavy emphasis on gothic horror — a whopping six of these issues have to do with possession by witches, ghosts, or demons, which I suspect might be writer Bob Haney testing the bounds of the weakening Comics Code Authority, which previously banned such ilk. One truly appalling story has Mal pursued by the ghost of an antebellum slaver, while the rest of the team is deeply unhelpful — check out a fascinating deep dive here. But almost none of the stories have any sort of socially relevant or activist angle, and the ones that do are so toothless as to be meaningless. In one story, a successful businessman who hates criminals and doesn’t believe in reform is revealed to have been a former thief himself; in another, Kid Flash tours a college he’s considering attending and discovers that the students are being subjected to involuntary brain surgery to make them complacent. The most “political” story comes in #37, when the Titans learn that their good friend Grady Dawes, a young and dashing video journalist who we’ve literally never heard of before, has gone missing while covering the civil war in “Ranistan.” The Titans try to rescue him, but are thwarted by the actual Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and Grady is accidentally shot to death. Throughout, the story aggressively refuses to take a point of view: we have no idea what the war is about, and the Titans aid both “the government” and “the rebels” indiscriminately, while the U.S. government refuses to intervene — you know, like the U.S. so often does. The closest Haney comes to taking a stance is Robin’s bold declaration that “War is stupid.” Bold words, Grayson, bold words. Even Mr. Jupiter largely recedes in the background, except to provide the resources to allow the Titans to globetrot. That is, except for #38, in which he decides that Robin, Wonder Girl, and Mal need to overcome their subconscious fears, so he disguises himself as a balloon seller and sells them each a balloon filled with hallucinogenic gas that will force them to confront their worst nightmares. Definitely a regular and not at all cult leader-y thing to do! Reading this era of Teen Titans, I can’t help comparing it to the famous Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams, which were being published at the same time. Dated and hokey as the GL/GA comics can seem today, they had a clear point of view, and specifically named the issues they wanted to engage with: racism, classism, pollution, exploitation of the working class, and the places all those issues intersect. Teen Titans, by contrast, falls flat because it is unrelentingly nonspecific. We don’t know why Dr. Swenson won the Nobel Peace Prize or why he was so beloved; we don’t know what social ills Jupiter wants to combat (which only helps to make him come across more like a creepy puppet master than a philanthropist). Every so often Mal will accuse someone of racism, but he’s generally completely ignored by the entirely white cast, making him seem paranoid rather than perceptive. The few stances the Titans do take are things very few people would disagree with, like “it’s sad when nice people die,” “hypocrisy is bad,” “lobotomizing students is also bad,” and, of course, “war is stupid.” More than anything else, it feels like the creative team understood that young people in the real world were upset, but either didn’t understand or agree with why, and offered up this milquetoast response in a half-assed attempt at seeming “relevant.” But I don’t really care how many random witch and ghost possessions the Teen Titans overcome when the word “Vietnam” never once appears. Teen Titans was canceled after issue #43 (January–February 1973), then briefly resurrected in 1976, picking up the same numbering, only to be canceled again in 1978 at issue #53. The franchise would get a drastic makeover in 1980 with the launch of Marv Wolfman and George Perez’s New Teen Titans, which was more concerned with baroque superhero drama than social justice, but still did a much better job of being something teens could relate to and connect with. Mal Duncan remained sidelined and marginalized until…well, this year, arguably, when he was featured in issue #2 of John Ridley and Giuseppe Camuncoli’s remarkable The Other History of the DC Universe, which retells those ’70s adventures from Mal’s perspective; I highly recommend picking up a copy, and really the whole series. Lilith was killed off for a while in the early 2000s, but she’s been back since 2016; Gnarrk was killed off in Heroes in Crisis in 2018. Mr. Jupiter, meanwhile, pretty much vanished until 1996, when he popped up to once again bankroll a very different lineup of Titans. It was also finally revealed that he was Lilith’s father, unbeknownst to her and despite the fact that she spent most of the 1970s desperately trying to figure out who her parents were, a fact he was well aware of. Stay creepy and manipulative, Jupiter! Ultimately, the early ’70s Teen Titans is an interesting cultural artifact, but one that’s more interesting for the ways in which it fails than anything else. If you’re looking for a story about what teenagers actually cared about in the early ’70s, you’ll have to look outside of DC’s teen stories. But hey…we’ll always have the Canary Cottage!