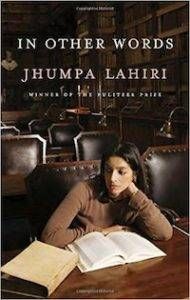

Reading In Other Words, I found myself overcome with two feelings. One: guilt for not knowing another language fluently. Two: familiarity at Lahiri’s frustrations and triumphs in learning a new language. In theory, I should be fluent in Spanish. I am not. My Spanish is babyish, naming random objects and answering simple questions. When I attempt to speak Spanish, I feel like I am drowning. I revert to one-word sentences, or answer in English. Even when speaking Spanish with my own grandmother, I cannot reach the bottom of the lake for safety. Spanish should be one of my mother tongues, alongside English. The same way my father spoke as a child. I could study and practice and work hard to become fluent, but Spanish will never belong to me the way it belongs to my father or grandmother. My father stopped speaking Spanish as a child and only returned to it as an adult out of necessity. Spanish was not spoken in my home until I could read and write, my learning window already passed. I never understood why my father never taught my brothers and I Spanish. Then, he told me that speaking Spanish was punished when he was in school. Children of immigrants, like Lahiri, experience shame for being other, their mother tongue ostracized rather than celebrated. In Other Words is printed in Italian and English, side by side. Lahiri originally wrote it in Italian while living in Rome. She kept journals written in Italian, scribbling new vocabulary words on every page, and struggling with verb conjugation. Then, eventually, describing the surprise from others that she speaks Italian and speaks it well. I have the opposite reaction in my life. Shock, confusion, and even anger at the fact that I, a brown-haired, brown-eyed, olive-skinned person in Texas, cannot speak Spanish. I’ve stumbled through awkward customer interactions at various jobs, feeling insufficient. On a trip to Mexico City in 2016, I felt more uncomfortable attempting my babyish Spanish with cousins and their friends than I did speaking absolutely horrific Cantonese in Hong Kong. Perhaps it was the lack of expectation I had for myself in Hong Kong. I’d never studied the language before and could only recognize a small set of sentences. Spanish, though, I’ve studied. I’ve worked on. I learned to read in a Mexican kindergarten class. I spent four years studying Spanish in high school. After college, I tried working on my Spanish again, but getting frustrated with my lack of progress. Reading Spanish is difficult, but doable. I can listen to conversations in Spanish and follow them, but I cannot contribute much. When I watch Spanish movies or television, I only need to glance at the subtitles occasionally. Still, I cannot claim any semblance of fluency. If I were to move to a Spanish speaking country, I would hope that my Spanish would improve dramatically. Not without effort, of course. In Rome, Lahiri stopped speaking English entirely. She read and wrote solely in Italian, even in her emails and notes. Lahiri and her husband, who is a native Spanish speaker, conversed in Italian in public and at home. I envy Lahiri’s love of Italian. To be transparent about her fluency, Lahiri did not translate In Other Words herself. How many readers, outside of Italy, would know the difference? The translation of Lahiri’s young Italian gives readers a sense of the vulnerability that Lahiri felt living in Rome. It is like being in that dark lake with her. Speaking a foreign tongue with native speakers is terrifying. I feel stupid and incapable speaking Spanish. Then, I swim a little further. No one is laughing at me. I swim a little further. My cousins encourage my meager Spanish. I swim a little further, my feet can almost touch the ground. A woman smiles at me when I give directions to the gas station in Spanish. I swim a little further. I am standing on the shore again.