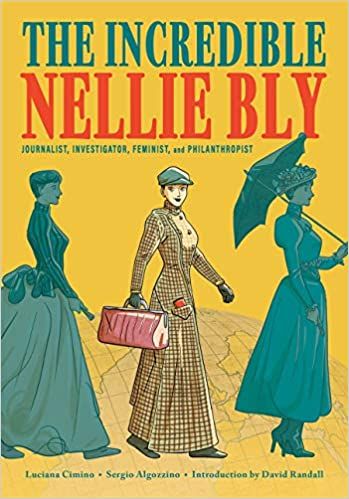

Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran in 1864, she was one of five children between father Michael Cochran and mother Elizabeth Cochran. Her father died when she was six, and money remained a challenge for the family thereafter. It was an article in the local Pittsburgh Dispatch where Bly got her start in writing. The piece, which suggested women were good for housekeeping and child birthing, led Bly to writing a response, and the paper’s editor, impressed with her writing, offered her an opportunity to write some more. Again impressed, the editor offered her a full-time position when he recognized that Bly’s arguments — which focused on labor reform and gender reform, among other progressive issues — and because it was customary for women to take on a pen name when publishing in a newspaper, she was given the name Nelly Bly (misprinted as Nellie, but kept as such thereafter). Bly’s work was investigative and groundbreaking, and the response that the paper received from her columns led to her career taking off. She served as a foreign correspondent at the age of 21, covering Mexican politics and culture, and her work, which was published later in a book, upset many government officials in Mexico because she sympathized with those whose voices were being suppressed by the country’s dictator. Though response to her work was tremendous, because she riled up factory owners and others with authority for her unflinching reports on working conditions, she found herself periodically reassigned to more “appropriate” topics, including fashion, arts, and theater. Bly’s passion for exposing truths couldn’t be suppressed though, and she left her role at the Dispatch. She welcomed herself into the office of John Pulitzer, owner of the New York World, hoping for a job. She got it, and that work would turn into her explosive look at the conditions in New York City’s Mental Health Hospital on Blackwell Island. She went undercover, pretending to be a mentally ill woman, so she could interact first hand with the workers, owners, and residents of the facility. It was but one of the major stories of Bly’s career, which spanned decades and helped spawn an entire industry of girl reporters (“stunt reporters”). In the below-noted Sensational, it’s made clear that even as the opportunity for women to break into hard news occurred in this period of American journalism, they were still belittled, still seen as lesser, by the simplicity of what their job titles were — stunts. These reporters made their papers big bucks, encouraging wilder and wilder reports and experiments (see Bly’s competition with Elizabeth Bisland on who could travel the entire world by boat first and fastest). This is but the tip of Bly’s story. In honor of the anniversary of her death 100 years ago and the legacy she created, here are some outstanding books about Nellie Bly to dig into. These books are going to be very white on account of Bly being white, but I want to highlight Sensational here again: this text does a stellar job of noting that white women were not the only “stunt” reporters, but they were the most “accepted,” and often, because of the use of pen names, women of color doing this reporting were either unknown or have yet to be given full-fledged articles and books of their own. This particular book certainly showcases Bly, but it’s essential reading for understanding the particular U.S. historical moment culturally and for women, laborers, and the journalism machine more broadly. Books included span age categories, from picture books to adult nonfiction, as well as format, from traditional prose to comics. There are novels in here as well, wherein Nellie plays a lead character. Because she died before public domain laws went into effect, her likeness and works were unable to be protected, which presents both a host of opportunities for creativity, as well as some challenges (see: this bizarre cover for Bly’s seminal work).

Book About Nellie Bly

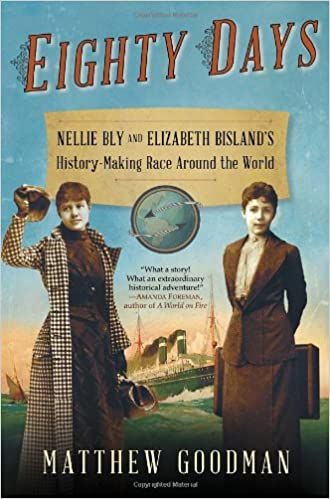

Books by Nellie Bly

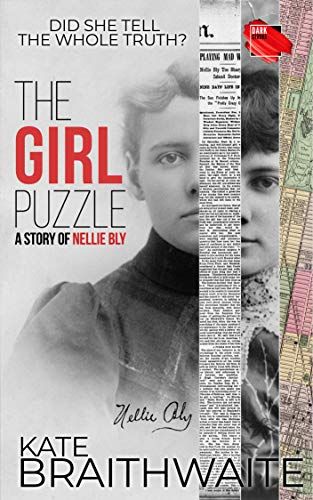

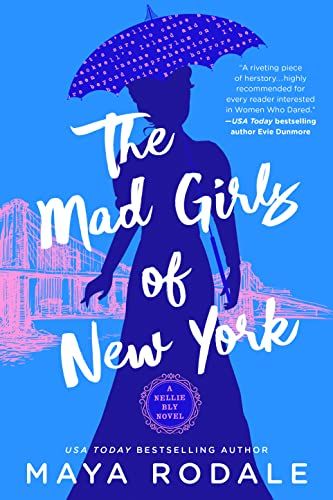

Bly’s most well-known writing explored the conditions of Blackwell Island, and if that’s a topic that fascinates you, check out Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal by Stacy Horn that offers insight into Bly’s work and the grander picture of mental health, institutionalization, and abuse during the late 19th century in New York City. The same day, Elizabeth Bisland left on assignment from a rival paper, hoping to do the same in her trip around the world. They went opposite ways, and the two journalists were a study in contrasts. Goodman shares the highs and lows of the expedition for each reporter. Again, reiterating: this is fiction. But it’s a fun and interesting “what if?” Also, this is the book where I first learned (and fell in love with the fact) Nellie had a pet monkey named McGinty, picked up on her round-the-world trip, and he broke all of her dishes after their voyage around the globe. Note that the writing here talks in depth about the terrible mistreatment of people with mental illness and doesn’t shy away from highlighting that abuse. For more great reads on women in history, dive into these queer women’s history reads, these women’s history reads, and this feminist library history. Deep dives into a single woman’s life your jam? You’ll want to read about situating white women’s history in context (especially how it relates to Laura Ingalls Wilder) and a look at what it means to “uncover” the “truth” behind an artist like photographer Vivian Maier.