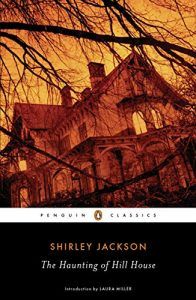

From Cherie Priest, author of The Family Plot and Maplecroft, comes The Toll, a tense, dark, and scary treat for fans of the strange and macabre. Titus and Melanie Bell are en route to the Okefenokee Swamp cabins for a honeymoon canoe trip. But just before they reach their destination, the road narrows into a rickety bridge with old stone pilings and room for only one car. Then Titus wakes up in the middle of the road, no bridge in sight. Melanie is missing. When he calls the police, they tell him there is no bridge on Route 177… I was 20 the first time I read Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. It scared the pants off of me. It continues to scare the pants off of me more than 20 years later. (Really, I just hate wearing pants, but it is very scary.) Get your scaredy-pants on (off?) with these 48 terrifying The Haunting of Hill House quotes. As these quotes are from the entire novel, there may be spoilers for The Haunting of Hill House.

48 Terrifying The Haunting of Hill House Quotes

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Eleanor Vance was thirty-two years old when she came to Hill House. The only person in the world she genuinely hated, now that her mother was dead, was her sister. During the whole underside of her life, ever since her first memory, Eleanor had been waiting for something like Hill House. Duty and conscience were, for Theodora, attributes which belonged properly to Girl Scouts. The light changed; she turned onto the highway and was free of the city. No one, she thought, can catch me now; they don’t even know which way I’m going. Because this was a time and a land where enchantments were swiftly made and broken she wanted to linger over her lunch, knowing that Hill House always waited for her at the end of her day. “She wants her cup of stars.” Exorcism cannot alter the countenance of a house; Hill House would stay as it was until it was destroyed. “I don’t stay after I set out dinner,” Mrs. Dudley went on. “Not after it begins to get dark. I leave before dark comes.” “I know,” Eleanor said. “We live over in the town, six miles away.” “I understand.” “We couldn’t even hear you, in the night.” “I don’t suppose—” “No one could. No one lives any nearer than the town. No one else will come any nearer than that.” “I know,” Eleanor said tiredly. “In the night,” Mrs. Dudley said, and smiled outright. “In the dark,” she said, and closed the door behind her. I am like a small creature swallowed whole by a monster, she thought, and the monster feels my tiny little movements inside. “No,” she said aloud, and the one word echoed. Journeys end in lovers meeting, she thought; it was my own choice to come. “Wait till you see the bedrooms,” Eleanor said. “Mine used to be the embalming room, I think.” “It’s the home I’ve always dreamed of,” Theodora said. “A little hideaway where I can be alone with my thoughts. Particularly if my thoughts happen to be about murder or suicide or—” “You’re frightened,” Theodora said, watching Eleanor. […] “It was just when I thought I was all alone,” Eleanor said. […] “I’m here now,” Theodora said, “so it’s all right.” “In the night,” Mrs. Dudley said. She smiled. “In the dark,” she said, and closed the door behind her. “You know,” Theodora said slowly, “up until the last minute—when I got to the gates, I guess—I never really thought there would be a Hill House. You don’t go around expecting things like this to happen.” “But some of us go around hoping,” Eleanor said. “Hill House has a reputation for insistent hospitality; it seemingly dislikes lettings its guests get away. The last person who tried to leave Hill House in darkness—it was eighteen years ago, I grant you—was killed at the turn in the driveway, where his horse bolted and crushed him against the big tree.” Eleanor thought with a little shock of surprise that she had only been at Hill House for four or five hours, and smiled a little at the fire. “Hill House, whatever the cause, has been unfit for human habitation for upwards of twenty years.” “It’s harder to burn down a house than you think,” Luke said. “Gossip says she hanged herself from the turret on the tower, but when you have a house like Hill House with a tower and a turret, gossip would hardly allow you to hang yourself anywhere else.” “It watches,” he added suddenly. “The house. It watches every move you make.” And then, “My own imagination, of course.” “Suppose we want to break out?” Eleanor asked. The doctor glanced quickly at Eleanor and then away. “I see no need for locking doors,” he said quietly. As she closed the door of the blue room behind her Eleanor thought wearily that it might be the darkness and oppression of Hill House that tired her so, and then it no longer mattered. “Nervous?” the doctor asked, and Eleanor nodded. “Only because I wonder what is going to happen,” she said. “So do I.” The doctor moved his chair and sat down beside her. “You have a feeling that something—whatever it is—is going to happen soon?” “Yes. Everything seems to be waiting.” “Promise me absolutely that you will leave, as fast as you can, if you begin to feel the house catching at you.” “Coming, mother, coming,” Eleanor said, fumbling for the light. “It’s all right, I’m coming.” Eleanor, she heard. Eleanor. “Coming, coming,” she shouted irritably. Just a minute, I’m coming.” “Eleanor?” Then she thought, with a crashing shock that brought her awake, cold and shivering, out of bed and awake: I am in Hill House. “Maybe it will go on down the other side of the hall,” Theodora whispered, and Eleanor thought that the oddest part of this indescribable experience was that Theodora should be having it too. “No,” Theodora said, and they heard the crash against the door across the hall. It was louder, it was deafening, it struck against the door next to them (did it move back and forth across the hall? did it go on feet along the carpet? did it lift a hand to the door?), and Eleanor threw herself away from the bed and ran to hold her hands against the door. “Go away,” she shouted wildly. “Go away, go away!” All of them stood in silence for a moment and looked at HELP ELEANOR COME HOME ELEANOR written in shaky red letters on the wallpaper over Theodora’s bed. “Nell?” Theodora looked up at her and smiled. “I really am sorry, you know,” she said. I would like to watch her dying, Eleanor thought, and smiled back and said, “Don’t be silly.” Now, Eleanor thought, perceiving that she was lying sideways on the bed in the black darkness, holding with both hands to Theodora’s hand, holding so tight she could feel the fine bones of Theodora’s fingers, now, I will not endure this. They think to scare me. Well, they have. I am scared, but more than that, I am a person, I am human, I am a walking reasoning humorous human being and I will take a lot from this lunatic filthy house but I will not go along with hurting a child, no, I will not; I will by God get my mouth to open right now and I will yell I will I will yell “STOP IT,” she shouted, and the lights were on the way they had left them and Theodora was sitting up in bed, snarled and disheveled. “What?” Theodora was saying. “What, Nell? What?” “God God,” Eleanor said, flinging herself out of bed and across the room to stand shuddering in a corner, “God God—whose hand was I holding?” I am learning the pathways of the heart, Eleanor thought quite seriously, and then wondered what she could have meant by thinking any such thing. They perceived at the same moment the change in the path and each knew then the other’s knowledge of it; Theodora took Eleanor’s arm and, afraid to stop, they moved on slowly, close together, and ahead of them the path widened and blackened and curved. On either side of them the trees, silent, relinquished the dark color they had held, paled, grew transparent and stood white and ghastly against the black sky. The grass was colorless, the path wide and black; there was nothing else. […] then Theodora screamed. “Don’t look back,” she cried out in a voice high with fear, “don’t look back—don’t look—run!” And, holding Theodora, Eleanor looked up at Luke and the doctor, and felt the room rock madly, and time, as she had always known time, stop. Idly Eleanor picked a wild daisy, which died in her fingers, and, lying on the grass, looked up into its dead face. There was nothing on her mind beyond and overwhelming wild happiness. She pulled at the daisy and wondered, smiling at herself, What am I going to do? What am I going to do? Without a word Theodora took up the quilt from the foot of the doctor’s bed and folded it around Eleanor and herself, and they moved close together, slowly in order not to make a sound. Eleanor, clinging to Theodora, deadly cold in spite of Theodora’s arms around her, thought, It knows my name, it knows my name this time. The pounding came up the stairs, crashing on each step. It is so cold, Eleanor thought childishly; I will never be able to sleep again with all this noise coming from inside my head; how can these others hear the noise when it is coming from inside my head? I am disappearing inch by inch into this house, I am going apart a little bit at a time because all this noise is breaking me; why are the others frightened? “[…] Hill House is not forever, you know.” “I can get a job; I won’t be in your way.” “I don’t understand.” Theodora threw down her pencil in frustration. “Do you always go where you’re not wanted?” Eleanor smiled placidly. “I’ve never been wanted anywhere,” she said. I have waited such a long time, Eleanor was thinking; I have finally earned my happiness. She heard clearly the brush of footsteps on the path and then, standing back hard against the bank, heard the laughter very close; “Eleanor, Eleanor,” and she heard it inside and outside her head; this was a call she had been listening for all her life. None of them heard it, she thought with joy; nobody heard it but me. Funny, Eleanor thought, going soundlessly in her bare feet down the hall carpet, it’s the only house I ever knew where you don’t have to worry about making noise at night, or at least about anyone knowing it’s you. No stone lions for me, she thought, no oleanders; I have broken the spell of Hill House and somehow come inside. Eleanor laughed. “But I can’t leave,” she said, wondering where to find words to explain. She might have cried if she could have thought of any way of telling them why; instead, she smiled brokenly up at the house, looking at her own window, at the amused, certain face of the house, watching her quietly. The house was waiting now, she thought, and it was waiting for her; no one else could satisfy it. I really am doing it, she thought, turning the wheel to send the car directly at the great tree at the curve of the driveway, I am really am doing it, I really am doing this all by myself, now, at last; this is me, I am really really really doing it by myself. Hill House itself, not sane, stood against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, its walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone. The Creepy, Fantastic Covers of The Haunting of Hill House 13 Spooky Books Like The Haunting of Hill House How The Haunting of Hill House Has Shaped Our Idea of Haunted Houses